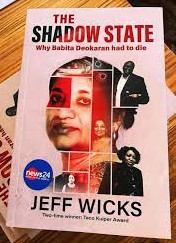

Jeff Wicks, The Shadow State: Why Babita Deokaran had to Die (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2025)

WHETHER South Africa is already, or is becoming, a mafia state is a matter for debate. Corruption on a grand scale is pervasive, eating away at every level of government. Not only is it morally unacceptable, but it widens the gaps between haves and have-nots by privatising national resources. It is not just a crime; but one that amounts to socio-economic treason.

There is a thin and vulnerable frontline protecting the nation from this scourge. A major part of it consists of whistleblowers, a few diligent police and investigative journalists; all of whose consciences and sense of duty overcome the very real danger they face. Three of the them star in this book: Babita Deokaran who fingered mass corruption in the Gauteng health department (the largest provincial department in the country by budget but a ‘den of corruption’); Freddie Hicks, an old-style police officer; and journalist Jeff Wicks. The first is dead, the second retired and the third has produced this brave book.

Deokaran died on 23 August 2021 in a drive-by shooting having delivered her daughter to school. She was an exemplary senior civil servant from humble beginnings in Phoenix who had hawked samoosas and worked as a volunteer at the House of Delegates before obtaining a diploma in finance.

Six izinkabi (hitmen) were convicted after a plea bargain. But the initial police reaction was one of gross negligence in which Deokaran’s car and possessions were rescued by her family. Murder had been committed, but there was no crime scene until Hicks and his team arrived. Use of private security company cameras led to the detention of a suspect who identified a house in Rosettenville where five more arrests were made.

The case was handed to the Hawks. They freed other suspects including the probable assassin who conveniently died later in what was described as taxi violence. The BMW and weapons related to the shooting disappeared. Effectively this is now a cold case with six men in jail. The outcome of their plea bargain was greeted with jubilation: masterminds support their gunmen’s families, probably with funds stolen from the public, in exchange for silence. A telling factor was the high-powered legal team used by supposedly poor izinkabi. Wicks visited Nhlawe near Weenen, a breeding ground of assassins linked to the taxi industry where the hitmen had sought the protection of muti, but made no progress.

The question Wicks has clearly answered, however, was why Deokaran had been killed. Inexplicably the Hawks handed back her laptop and phone and these were unlocked by a private firm, providing damning evidence. A spreadsheet showed that from April to July 2021, 2 453 transactions had been processed for Tembisa hospital alone, taking the lion’s share of the budget. A giveaway was the fact that all of the orders were for just under R500 000, the upper threshold for in-house decisions. Deokaran had stopped R104 million in dodgy payments, identified 217 suspect companies, and requested a probe into R1 billion of expenditure. One firm tendering for medical equipment was an events management company called Kaizen linked to an ANC politician. Deokaran’s red flag was ignored. She clearly recognised the danger she was in and unwisely expressed fears to her line manager. Auditors posthumously backed her.

Whether the Hawks were simply incompetent or complicit, or both, it was clear that Wicks was now doing police work in order to continue what Deokaran started. Covid-19 procurement had provided a wonderful opportunity for yet another cycle of looting based on emergency funding and extra-lax controls. Two viruses were at work, medical and moral, assisted by the practice of political appointments that resulted in fifth-rate hospital leadership.

The suspect companies flagged by Deokaran had meaningless names, fake addresses and fake directors (one was found living in a RDP house and working in a factory); and were engaged in rigged bidding through means such as split invoicing that achieved a predetermined outcome. Handpicked bidders were in fact all controlled by one person. Supposed barriers to fraud failed utterly: one order had seventeen irregularities that apparently went undetected. This was assisted by a system that to this day is paper-based and easily manipulated by well-entrenched staff. If necessary, records could be incinerated through arson as indeed happened at Tembisa in April 2025.

What Wicks eventually uncovered was a system of fronting for three main syndicates, or medical supply dynasties, that were controlling orders, inflating prices and ultimately draining public funds to the detriment of patient care. This was not random, but heavily networked, corruption. One syndicate was run by Morgan Maumela who had a property portfolio, the lifestyle of the sort flaunted on that obnoxious TV programme ‘Top Billing’ and high-level ANC connections. Together three syndicates (the others belonging to Stefan Govindraju and Rudolf Mazibuko) took R1 billion in business over two years for sub-standard outcomes.

Wicks reminds his readers that the resulting lifestyles are enabled by lawyers, estate agents and car dealers as well as bent police and hitmen. And in this case the syndicates were assisted by Tembisa hospital’s CEO, Ashley Mthunzi, and his wife who ran an in-house union that threatened disruption. The ANC was involved via pressure exerted by the Progressive Business Forum. Mthunzi and the CFO Lerato Madyo were eventually suspended and took another R5.5 million in salary before Mthunzi died and Madyo was allowed to resign and then changed her name. Unsurprisingly, it was found that Mthunzi’s appointment was irregular.

Another name to emerge from this sewer of corruption, threats and violence was Vusimusi Cat Matlala, an elusive character apparently running a security company who was constantly on police radar. Yet, while under investigation for fraud he scored another contract – with the police. His wife uses a blue light to get their children to school on time. There is a link here to the suspended national head of detectives, Shadrack Sibiya.

In September 2023 the Justice Department’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU), which protects the public fiscus (over nine years it has retrieved R137 billion and averted another R34 billion of potential losses), at last started investigating Tembisa hospital, a captured contract factory. It found that the reach of the kingpins was widespread. Exactly how a national health service can be based on such foundations is hard to imagine.

Jeff Wicks makes frequent mention of his personal safety, something that might be frowned upon from a journalist; but he is correct to do so. Since Deokaran’s death at least nine other people exposing corruption have been murdered, the latest just this month, although none of them to date has been a journalist. He argues that publication is a form of protection and drip-fed stories as his investigation proceeded. Nevertheless, the tension affected his personal life and he ended up with a bodyguard; as indeed did the prosecutor in the case of the six inzinkabi. Since the proportion of bent police is large, good officers work in tight groups and detectives have to be housed in guarded safe houses. Wicks also assisted the SIU with information; again, not standard practice. But in the circumstances, a country increasingly run by violent criminals, convention should be reassessed.

This is what happens in a Leninist state in which party and government are interchangeable and eventually become inextricable. State capture is associated with the corrupt Zuma regime and its friends the Guptas enabled by the hollowing out of oversight institutions. It was exhaustively chronicled by the Zondo Commission, but led to not a single conviction. Since the demise of the Zuptas, state capture has become more insidious, pervasive and normalised. And as Deokaran and others have discovered, it is increasingly backed by lethal violence; a mafia state indeed.

Footnote: On 17 September 2025, Cat Matlala, facing murder charges, was denied bail.