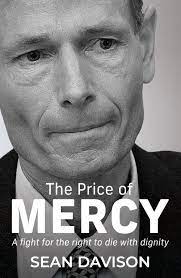

Shaun Davison, The Price of Mercy: A Fight for the Right to Die with Dignity (Cape Town: Melinda Ferguson Books, 2022)

AN OLD woman suffering from terminal cancer in New Zealand in 2010 decides to bring her life to an end through starvation. It’s an unwise choice, particularly surprising since she is a doctor. Her son, visiting from Cape Town, helps her with a lethal dose of morphine. The son, the now-famous Sean Davison, is a biotechnologist at the University of the Western Cape. One of his sisters later shops him to the police and he is charged with attempted murder, but a plea bargain sees him sentenced to five months house arrest. This is all well-covered in the South African press.

Back home in South Africa Davison is a founder of Dignity SA campaigning for a change in the law regarding assisted suicide for those whose physical and psychological suffering is too great to sustain a will to live. This includes the extremely aged, the terminally ill, quadriplegics and those with locked-in syndrome; some of them the sort of people who talk about ‘a living hell on Earth’ or existence ‘attached to a corpse’. But instead of simply lobbying, Davison became personally involved with a number of those wanting to die; and provided means and assistance. The exact number is not revealed but a central figure of this book is Anrich Burger, paralysed in a road accident. Like Davison’s mother he, too, is a doctor and after exploring various options he is helped by Davison to die in a Cape Town hotel room in 2012.

Five years later Davison is arrested and charged with premeditated murder. Two similar charges are later added with the daunting potential for three life sentences. Davison is clearly a man of great intelligence and resourcefulness with compassion and empathy to match who reasons that his knowledge and practical ability should be put at the service of the suffering. But to the semi-detached observer this often appears foolhardy. Davison has a partner and a young family of three children. It seems that he suffers from claustrophobia with a below-average tolerance for incarceration in a cell. The most valued part of his wellbeing is daily exercise with canine companions on Table Mountain. Yet he took various chances for relative strangers in the name of humanity that could have had dire consequences. Then, he risked infringing his bail conditions in a clearly fruitless pursuit of a Johannesburg crook peddling fake nembutal. Exactly why he was so reckless remains somewhat opaque.

It is no surprise that the police emerge poorly from this extraordinary saga. On the day of Davison’s arrest, they seized his tenant’s computer equipment giving him the opportunity to destroy evidence at his adjacent flatlet. Nor did they find nembutal he was able to bury in his garden. Why they waited five years before laying the first charge is unknown. But it might have something to do with UWC’s Innocence Project run from Davison’s DNA forensic laboratory. This had another look at DNA evidence in criminal cases with a view to the exoneration of the wrongly convicted. One example of embarrassment for the police were three separate rape convictions with identical DNA. Conversely during Davison’s three-year South African house arrest they were remarkably efficient at picking up minor infractions, although he was not fitted with a tracking device as in New Zealand. All this in a country drowning in violent crime and corruption in pursuit of a man exercising his admirable conscience to help those in extreme distress but unable to help themselves.

The contrasts are stark and bizarre. As for doctors, Davison acknowledges that some quietly involve themselves in assisted dying where the patient is well-known to them. Others preside over long-term suffering. And the profession as a whole has failed to make much impression on the debate around progressive change to the law although it is in possession of a wealth of pertinent knowledge.

At all stages of his confrontations with the New Zealand and South African authorities Davison had the invaluable support of Desmond Tutu, who recorded that he might request assisted dying for himself; and of UWC’s vice-chancellor Brian O’Connell. At one point it was possible that Tutu, through his knowledge of an intended mercy killing, might be open to a charge of complicity, although this would have been highly risky for police and state.

In spite of the stress through which he was put, Davison was remarkably fortunate. With charges stacking up against him, he was able to obtain and sustain bail, and then consider a plea bargain. While this involved admission of guilt it kept him out of jail. Instead, he served a three-year house arrest that allowed him to go to work and a five-hour Saturday break; accompanied by hundreds of hours of community service cleaning government offices and toilets. This came to an end in mid-2022 meaning that much of it took place under Covid-19 restrictions.

While serving his South African sentence, handed down as it happened by one John Hlophe, Davison was investigated by the New Zealand medical authorities which have jurisdiction over foreign cases. They vindictively concluded that Davison was guilty of professional misconduct meaning that job opportunities in his native country have now vanished. Yet with high irony New Zealand law has recently changed following a referendum meaning that the assistance he gave his mother (and by implication in the South African cases) is no longer illegal and he awaits a royal pardon from the governor-general.

The cause of assisted suicide seems crystal clear and the equation of euthanasia and murder a legal nonsense. It is easy to see why Davison and millions of other people support Dignity SA and Exit International. But he remains an enigmatic and complicated character, almost a stranger in his own book. Perhaps that was his intention. Davison has researched in the field of cognitive neuroscience exploring the rationality of suicide under certain circumstances. When South African law matches New Zealand’s his academic work and practical efforts, and the support of that great South African Desmond Tutu, will have been vindicated.