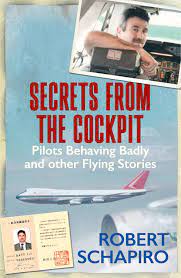

Robert Schapiro, Secrets from the Cockpit: Pilots Behaving Badly and Other Flying Stories (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2021)

WHEN I was young, we dressed up in our best clothes to travel by plane. Passengers were treated with a great deal of care, airports were exciting places, and food on flights was good. Apart from a ban on smoking, flying in the last fifty years has gone from pleasure to purgatory. People are now treated like cattle, constantly herded through security checks and crammed together in germ-laden monster aircraft. Nine-eleven was responsible for much of this and by 2010, when Robert Schapiro retired, ‘bean-counters and lawyers [had become] dominant in the struggling aviation industry. Stuff we used to do routinely was now considered a firing offence or even a crime’ (p. 237).

Schapiro grew up in Cape Town, attended Herzlia and was conscripted at the age of 17. He had nursed from a very early age an ambition to be a pilot and this he achieved through determination and application, plus slices of fortune. He admits to having been a loskop, which did not bode well for an aspirant pilot. But he survived basic training and the abuse handed out to Jews in the army and was successful in achieving entry to the South African Air Force (SAAF). The powers-that-be were suspicious of those clearly using conscription to launch commercial flying careers, but Schapiro was accepted and even joined the permanent force, highly unusual for someone of his background.

Having trained on Harvards, he found himself at 20 flying C-47 Dakotas in the operational area for 25 Squadron. These aircraft were hardy but idiosyncratic, used for a multitude of purposes and in the Border War to supply forward bases and for occasional missions in Angola. His promotion to C-47 commander was rapid, a move that was not universally popular. He recalls the heavy drinking culture and conflicts with the army about loading weights and balance.

The transition from SAAF to South African Airways (SAA) was bureaucratically tricky, but he was accepted at the age of 21 after which the airline stopped recruiting for six years. It was ruled on the ground by members of the Broederbond and in the air by an elite group of pilots known as the Royal Family, many of them World War II veterans. All round it was an authoritarian culture, not just in flight but during stopovers. Again, there was a toxic drinking culture and some older captains were alcoholics. Wanting to make good use of overseas breaks, Schapiro was regarded as a Jewish oddity; but the end of the 1970s was to bring a new, more professional era.

Schapiro provides a particularly interesting account of the boycott days when SAA planes had to fly around the bulge of West Africa and use the airport at Ilha do Sol in the Cape Verde Islands. Flying crews changed over there, but this desolate spot had little to offer them. His flying career spanned major changes involving automation that phased out old-fashioned navigators and radically changed the work of flight planners. One computerised innovation was INS (inertial navigation system), developed by the US military with a built-in error factor for commercial use. This was not a problem, but it was possible to pass abeam of waypoints assuming that the aircraft was on track. On a flight from Mauritius to Perth, Schapiro and his crew found themselves 160 nautical miles off course and could have disappeared without trace into the southern ocean. Korean Airlines KAL007 was shot down because of a similar error.

SAA allowed a certain latitude. One flight from Cape Town to Bloemfontein was diverted via Kimberley after a ballot of passengers. Another flew over the Augrabies Falls in full spate. If the cabin crew reported rowdy behaviour, captains would reduce oxygen levels and temperatures to calm the situation. In those pre-9/11 days passengers would be invited into the cockpit. There was an element of cowboy flying, especially on short sectors with competition to set records. And even at the height of apartheid the cabins of commercial aircraft were unsegregated spaces.

SAA was the ‘ultimate boys’ club’ in which promotion depended on ‘dead man’s shoes’. Schapiro eventually became a Boeing 747 captain, but the airline was shrinking for various reasons and he transferred to Nippon Cargo Airlines, flying 747 freighters from New York to Narita via Anchorage. Retraining involved adaptation to Japanese culture, which allowed no latitude at all, with government inspectors treated as godlike figures. It eventually dawned that examinations were essentially formulaic, something to be navigated, after which gaijin (foreign) flying could resume. Schapiro nevertheless clearly appreciated the perfection of Japanese maintenance.

Flying at night over the Arctic in a Japanese freighter, Schapiro thought about the unlikely outcome of his boyhood dream. It took a physical toll and after a sinus operation he retired at the age of 54. Five years later he died of lung cancer, an ironic outcome for someone who had a lifetime aversion to smoking.

This is a book that will appeal to anyone with more than a passing interest in aviation. There is considerable technical detail, but it is presented in readable and digestible fashion and Schapiro had an ability to use analogy to good effect. For example, he depicts flying as a three-dimensional game of snakes and ladders with pilots requiring the imagination to place themselves in it and deploy the capabilities of their aircraft accordingly.

We need more books of this kind. This is the life story of an ordinary person whose everyday activity was beyond the experience of most of us. In that lies the fascination.