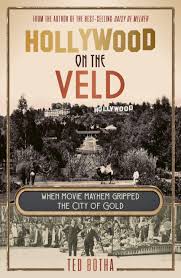

Ted Botha, Hollywood on the Veld: When Movie Mayhem Gripped the City of Gold (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2025)

RARELY can the central character of a book appear so elusive. The American Isidore William Schlesinger (IW) arrived in South Africa from New York in 1894 and made a fortune in insurance and property. Exactly how he did this is not known, but he later commented that he regretted not buying Golders Green (in London) in 1901. Small and secretive, he avoided the limelight but this was harder in the entertainment industry and there are recorded instances of unscrupulous behaviour. Anyone who amasses an enormous fortune rapidly is likely to be ruthless.

IW left no private papers and Ted Botha admits that piecing together a biography was a matter of guesswork and joining dots from memoirs, newspaper reports, entertainment magazines and the occasional court case. His privacy was protected by front men and his secrets went to the grave. Even as a film producer for a while, he remained in the shadows.

His business empire was based in Johannesburg at its most expansive and a population with ready cash and a need for entertainment. From 1913, IW started buying up theatres and then went into film production with African Films. In his insurance selling days he had travelled widely and developed a mystical view of South Africa that he termed a ‘wand of witchery’. His company produced the typical shorts of the time and documentaries. But he was most famous for filming on location using a monumental number of extras, especially Africans. Nothing was done by halves or spared expense.

He was competing with the Hollywood moguls and matched them in appearance, energy and wealth; single-minded, headstrong and very rich. His Parktown studios were a mirror of Hollywood; and Whitehall Court a blend of grand mansion and the hotels he favoured. And he married a film star, Mabel May. But his South African filming ended in the mid-1920s, excluded by the very Hollywood monopoly he had tried to impose and he moved his film business to London.

IW’s most famous films were Winning a Continent (about the Voortrekkers), the Symbol of Sacrifice (Anglo-Zulu War); and two based on Rider Haggard novels, King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quatermain (of the last there remains no trace). In tune with the over-blown language of the time there was a gung-ho approach to production that ignored health and safety. In the Voortrekker film there was a hazardous river crossing and a pitched battle staged at Elsburg near Johannesburg. The African extras, miners, were reportedly well briefed but their white opponents seemingly lost control. One African died. In the Anglo-Zulu War film, there were three more deaths in a river crossing that included Johan Colenbrander who had been a trumpeter at the battle of Gingindlovu. Haggard’s fiction required spectacular sets such as the Great Stairway of Milosis, built at a Johannesburg mine.

IW died in 1949, his multiple businesses still alive in South Africa. One of them became the South African Broadcasting Corporation. But the imprint of his film empire soon faded and today there is barely a trace of it. His obscure grave on a farm at Zebediela is a fitting monument to obsessive secrecy.

History is hard to record when subjects deliberately conceal themselves. But Botha is correct to lament the deterioration in libraries of newspaper holdings, which have not been digitised as they should have been. And the Jewish Archives in Johannesburg crucial to this research has simply been closed. The past is elusive; but it seems we are sometimes making its reconstruction all the more difficult.