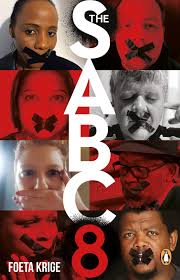

Foeta Krige, The SABC8 (Penguin, 2019) BOOKSHOP shelves are weighted with tales of anti-apartheid activism. And the number of titles recording the struggles of post-liberation human rights activists grows steadily. Foeta Krige’s book considers the shocking capture of the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) through the experiences of eight journalists (the SABC8, including him) who took on corrupt management. Significantly, the names of two prominent struggle families – Calata and Gqubule – link the pre- and post-1990 eras.

Capture of the SABC was nothing new: Snuki Zikalala did it for the Mbeki administration by blacklisting certain commentators. (With high irony, another of the SABC8 is Thandeka Gqubule, Thabo Mbeki’s sister-in-law.) But Hlaudi Motsoeneng, an ‘illiterate narcissist with a God complex’ in Krige’s opinion, went much further by treating the ethics of journalism, the SABC’s own code and the provisions of the Constitution with contempt. Motsoeneng enjoyed heavy political patronage, so his lack of required qualifications and inability to string together a meaningful coherent sentence were no bar to appointment to various managerial positions. He presided over almost R5 billion in irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure; including R21 million of his own illegal benefits.

Once he had become institutional dictator and political commissar, he undermined editorial independence, promoted sunshine (70% positive) journalism, banned coverage of protest action, and binned programmes that drew on other news organisations. Hypocritically he had close dealings with the Guptas’ New Age Media Group, to the SABC’s detriment but with the support of the communications minister and the ubiquitous Number One. Through high-profile enforcers and lower-key supporters, some of them white remnants of the apartheid regime, an atmosphere of fear designed to suppress dissent enveloped the organisation in the name of the ever-present transformation.

The South African Communist Party described a ‘despotic regime’ masterminded by a ‘dedicated liar’. Motsoeneng lived up to this billing by denying the concept of journalistic independence: SABC staff were destabilising the institution and must obey instructions (he even suggested a company uniform). But seven staff members questioned the ban on protest news and were suspended. A supportive freelancer had his contract terminated – and so the SABC8 was born. The policy against which they took a stand was later declared unlawful by the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa.

A Labour Court case reinstated all of them except Vuyo Mvoko, who was not permanent staff, although the SABC made their return as difficult as possible. They continued their plans to approach the Constitutional Court about editorial freedom especially in view of the anodyne findings in August 2016 of the parliamentary portfolio committee on communications. Parliament, however, redeemed itself by setting up an ad hoc committee of inquiry before which four SABC8 representatives testified. The broadcast proceedings of the SABC on trial gripped the country in December 2016. Gqubule, Mvoko, Lukhanyo Calata and Krivani Pillay graphically showed how the Broadcasting Act had been trashed, the SABC’s mandate betrayed, public service broadcasting demeaned, and professional ethics subverted by a toxic mix of political agenda, corruption and ruthless personal ambition. The inquiry’s findings totally vindicated the SABC8 and the responsible minister, Faith Muthambi, was branded incompetent.

But vindication, as tends to happen, came at a heavy price. All members of the SABC8 received death threats by SMS from six untraceable cell phones (so much for RICA). One of them, the youngest and most vulnerable, Suna Venter, an enigmatic and driven character, was subjected to an unrelenting and unbearable reign of terror. Her Johannesburg flat was attacked and trashed as was temporary accommodation in Stellenbosch; her car’s tyres were slashed and its brakes tampered with; and she was assaulted then shot at twice, once in the face. In an utterly bizarre incident this book fails to elucidate, she was kidnapped and tied to a tree at Melville Koppies around which the veld was set on fire. Just two of these incidents would have been beyond coincidence, but the police showed little interest. The content of the threats led to the inevitable conclusion that inside information was provided. And the professionalism of Venter’s harassment bears the prints of the State Security Agency.

The persecution continued. When Winnie Madikizela Mandela died, Thandeka Gqubule and two other journalists were accused by Julius Malema’s EFF of being Stratcom agents; in other words working on behalf of the apartheid government. Such is the price of standing by professional ethics and the spirit of the Constitution. Venter was found dead in her flat in June 2017 at the age of 32 from what is commonly known as broken heart syndrome.

In an emotional letter written shortly after her death, Krige, who was her boss at Radio Sonder Grense, vents his anger at the price she paid and the poor all-round support she had received; the rage of a man of conscience. While his book provides considerable background depth it is written from a particularly personal angle that will appeal to many readers. However, long chains of WhatsApp messages, while reflecting tensions, emotions and relationships, might have been abbreviated in some instances.

This book celebrates the ongoing spirit of human rights activism that now grapples with the toxic authoritarianism of the ANC and other South African political currents. But the sad truth is that South Africans no longer have a public service broadcaster in spite of the SABC’s claim under new management that it is ‘independent and impartial’. Its content now consists largely of pop music, interviews with politicians, phone-in programmes populated by ignorant self-publicists, and income-raising advertorial. The proportion of programming that informs and educates is in terminal decline. Motsoeneng gets the last laugh; another nail in the coffin of democracy. Happily, his African Content Movement scored a derisory 0.03% of the national vote in the 2019 general election.

In a broader sense many people who read this book will recognise their own experiences in other places, which have worn away at the creativity, initiative and work satisfaction that generate excellence. Too many people these days labour under incompetent and authoritarian management that crushes reasoned argument, despises professional standards, and promotes destructive agendas.