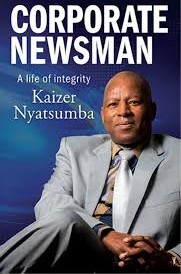

Kaizer Nyatsumba, Corporate Newsman: A Life of Integrity (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2025)

Autobiography, however nuanced, always involves a degree of self-indulgence. And all autobiography is by definition one-sided. This one tells the story of a man of very humble beginnings who through intelligence, hard work and determination became at a young age the first African editor of a mainstream South African newspaper.

Kaizer Nyatsumba grew up in the White River area, son of a Mozambican father, with an aunt and a cousin. His mother became a traditional healer. He completed his school education at Dlangezwa High near Empangeni having shown an aptitude for debating plus an excellent academic record. Outside school he worked as gardener, caddy and construction worker.

He was able to escape University of Zululand during the time of Inkatha-inspired disruption by gaining a scholarship at Georgetown University in the USA where he wrote poetry and was active in the anti-apartheid movement. Nyatsumba was fortunate that in the late 1980s South Africa was beginning to change significantly. He became a journalist at the Star and attended the Argus Cadet School.

Court reporting and book and theatre reviewing followed before he became the paper’s first black political reporter. He also appeared on radio and television. In 1995, Nyatsumba succeeded Shaun Johnson as political editor of the Star and three of his appointees rose to considerable prominence in the media.

His career shifted to Durban, including editorship of the Daily News, where he had to resist pressure from the ANC. He rose to considerable heights within the Independent Group, including two years in London that ended in dismissal in 2003. Subsequently he worked for a succession of big business outfits: Anglo American (particularly on sponsorship of South Africa’s bid for the 2010 FIFA World Cup); Coca Cola; Sasol; PetroSA; and finally the Steel and Engineering Industries Federation.

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of this book is the fact that while as a journalist he was a significant observer of key changes in late- and post-apartheid South Africa, he has little to say about them and foregrounds himself. His sole substantial account of Nelson Mandela relates to the latter’s attack on him and other independent-minded black journalists. However, his account of a brush with Mac Maharaj is very revealing.

But there is extensive coverage of the Human Rights Commission investigation into racism in the media to which many commentators unreasonably raised objections, although Nyatsumba is honest enough to note that its background research was truly atrocious.

He missed no opportunity to add to his academic and professional qualifications, ending up with a PhD in business administration focusing on airline turnaround; and as a chartered director and business rescue practitioner. He does not suffer from modesty and writes about his ‘national stardom’ (p. 127).

He also has much to say about his personal life and in greater detail than most readers would require. We also learn about every car he has ever owned. He was deserted by his first wife, but we lack her perspective; and he basically paid off a subsequent partner. He admits to a bumpy relationship with his son and offers only a part explanation. Such is autobiography.

Nyatsumba waits until the end of his book to inform readers that ‘I have never been anybody’s cadre or comrade’; and that ‘Education, experience, integrity and independence of mind are not of much value in our public sector’ (pp. 272‒273). In a nutshell that sums up the post-apartheid tragedy. This book provides an interesting perspective on modern South Africa, one that is strikingly different from the usual political narratives.

Nor is there reason to doubt the truth of the sub-title. But among many, mainly colour, photos it was perhaps unwise to include one picturing Danny Jordaan, Sepp Blatter and Essop Pahad with the author.