IT was the most banal of events: fifty years ago, in mid-October 1973, two cricket teams met in the local league in Alexandra Park, Pietermaritzburg. But one of them, Aurora, comprised players from different ethnic backgrounds. Among the spectators were at least ten police officers, one of them photographing cars, and their commander, Colonel J. Pieterse. The government had gone to the trouble of issuing Proclamation R228, which it imagined would prohibit the match.

Aurora claimed innocently that they were simply interested in cricket, but there was of course a political purpose. The object was to challenge the law, whose control of the use of public open space was contestable; apartheid policy; and long-accepted colonial custom. It was claimed, erroneously, that these factors ruled out mixed sport. Many of those involved with Aurora were lawyers with a contrary view. John Didcott famously advised, given the laws of apartheid, a defence strategy: to ‘bowl brilliantly, bat badly – and not stay for tea.’

They opted to challenge local white cricket administrators who, by and large, proved amenable. So did the municipality. But Minister of Sport Piet Koornhof attacked Aurora players as terrorists and agitators, although they were acting entirely within the law. He was boxed into a complicated corner, trying to restrict mixed sport while maintaining international links; and above all attempting to reassure National Party verkramptes.

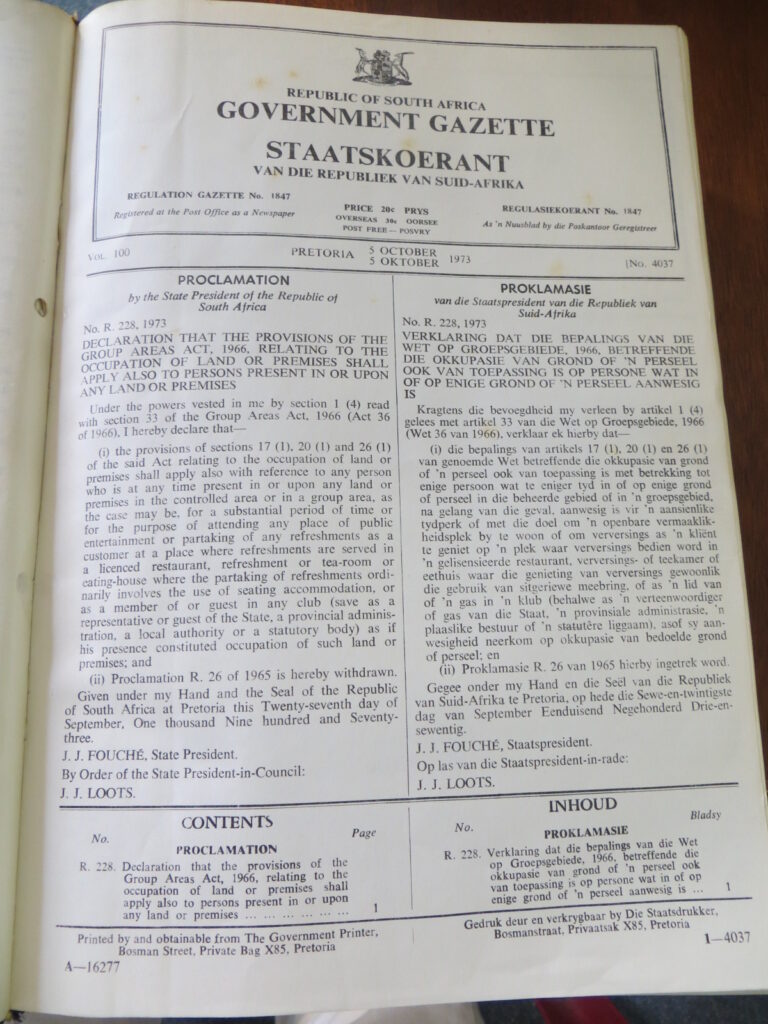

His proclamation in terms of the Group Areas Act referred to use of space over ‘a substantial period of time’; but was shoddy law, void for vagueness with many unintended consequences (nannies in white parks, for instance). Late in the day in Aurora’s first league match, Warrant Officer Boucher asked the Aurora captain Gopaul Manicum if he had a permit. The answer was negative so Boucher started taking names of players of both sides, the young scorer and his sister, and a dozen spectators.

It was one of apartheid’s more farcical events. No prosecution ensued, nor was there any real chance of the farce ending in Aurora’s banning. So, the team played on in the white league. What they had achieved was to break South Africa’s social geography that prevented ethnic mixing in a recreational context. Economic mixing had a long history, of course, but once social taboos were broken even apartheid law was no solution as Koornhof had found. This was especially important as the government was trying to establish ethnic, self-governing areas within cities. In Pietermaritzburg defined Indian and coloured cities would be overseen by local advisory committees.

Aurora had correctly assessed the limitations of the law and fragility of custom; and seized the moment with South Africa looking for international approval amid a growing boycott movement. The early 1970s were a significant time for political change often characterised by the Durban Moment: strikes that led to independent, non-racial trade unions flavoured by Steve Biko’s black consciousness and Rick Turner’s ideas about participative democracy. But the actions of Aurora also signal a Pietermaritzburg moment framed by municipal approval of limited desegregation, especially the Natal Society (public) Library now open to everyone. And in 1974 the independent non-racial Metal and Allied Workers Union (today NUMSA) was founded in Pietermaritzburg.

In 1978 Aurora took an even more significant step by exiting white cricket, which showed no real commitment to change except a return to international competition, and joined the non-racial Maritzburg District Cricket Union. This was affiliated to the South African Council on Sport (SACOS), coincidentally founded in 1973 to oppose discrimination in sport, but now after the Soweto Uprising of 1976 openly anti-apartheid. This move cost Aurora a few members unhappy about the move from white space to poor, and often non-existent, facilities in unfamiliar areas. But it positioned the club unequivocally as apartheid began to unravel.

Perhaps Aurora’s greatest achievement was to shed complacency, identify legal loopholes and opportunities, and act decisively in pursuit of a cause – first multiracial, then non-racial sport. On a far grander scale this was the essence of the Durban strikes and then the schoolchildren’s uprising in Soweto; making the 1970s a decade of profound change in South Africa often overshadowed by the dramatic events of the 1980s.

- The front page image shows Aurora players at a post-match celebration in 1982 or 1983.

- This piece was first published in the Witness in an earlier version dated 12 October 2024.