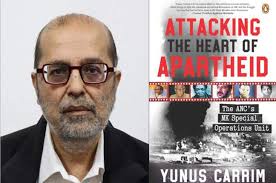

Yunus Carrim, Attacking the Heart of Apartheid: The ANC’s MK Special Operations Unit (Cape Town: Penguin, 2025)

MK’s Special Operations (Ops) unit emerged from a long debate within the ANC in exile about the role of violence in the anti-apartheid struggle. The regime was unlikely to be defeated by guerrilla warfare for a variety of factors, not least the country’s geography. So military action alone was no answer, although MK rank and file were agitating to return to South Africa to fight. If there were a point to violent action it had to be in the service of overall political aims and in sync with the other planks of ANC strategy: mass mobilisation, internal underground work and international support.

Thus, Special Ops, an elite force, was created to supplement the regional units that had conducted 82 attacks between 1977 and 1980. From 1980 it in turn planned 80 operations of which 72 were concluded, all but four in the Transvaal or Natal. The aim was the well-worn ANC tactic of armed propaganda; to stimulate and encourage opposition to the government and undermine rather than defeat it by what was disparagingly referred to as militaristic vanguardism. Thus, an emphasis on hitting economic infrastructure and the security forces.

Yunus Carrim identifies 93 Special Ops members, but suggests that many deaths and misidentification may require revision of this number. Between 2016 and 2024 he interviewed 48 people, some several times. He was not a member of MK, but of the ANC and SACP and a journalist and academic, so his standpoint is that of a very informed insider. The author takes particular care to emphasise that this is a partial account based on survivors of whom a disproportionate number are not African. Similarly, there are conflicting accounts based on memories of varying accuracy, plus press reports that must be treated with great circumspection. Perhaps the most striking survivor is the unit’s third commander, Aboobaker Ismail (Rashid), a complex individual who was a master planner and a stickler for detail and precision.

The first attacks were spectacular indeed and made a huge impression, not least for the impact of synchronised limpet mine explosions. These were not opportunistic or hit-and-run attacks but sophisticated, carefully planned operations involving dead-letter boxes for materiel and thorough surveillance and long-term planning. Sasol 1 and 2 and Natref were hit, symbolically on 31 May and 1 June 1980.The night before, in an act of extraordinary confidence, Barney Molokoane’s unit stayed in an empty police cell. At a time of tightening sanctions, attacking an oil-from-coal plant was deeply significant; as was the cause of South Africa’s biggest fire, a blaze that lasted three days seen far and wide. There was only one injury. The reaction was heightened security, national key points legislation and raids on Swaziland and Mozambique. The following year Sasol was hit again, this time by an insider in a solo effort that is not entirely clear.

MK Special Ops had arrived. The next action in July 1981, commanded by Johannes Mnisi, also involved three targets: power stations at Camden and Arnot and a sub-station at Delmas in Operation Blackout. Reconnaissance was long and detailed and extensive damage was done to transformers at a time of power shortages and the twentieth anniversary of the republic. Electricity infrastructure was a weak spot, but there was no follow-up because Eskom improved its perimeter fencing.

The following month an even more audacious attack was mounted on Voortrekkerhoogte military headquarters in Pretoria using a Grad-P rocket launcher. One hundred kilos of equipment was smuggled from Mozambique under a converted van and five rockets were fired on 12 August by Molokoane. Damage was limited, but the propaganda value colossal resulting in an attack on ANC premises in London.

The attacks are difficult to rank, but that on Koeberg nuclear plant on 18‒19 December 1982 had such an effect that years later government officials could not believe it was an ANC operation; blaming the German Baader Meinhof Group or someone from the French contractors. The timing was carefully chosen prior to nuclear commissioning and four limpet mines exploded in two control rooms and on two reactor heads. Stolen plans were delivered to the ANC in Zimbabwe by Rodney Wilkinson and Heather Gray who were then chosen as the saboteurs. The mines were picked up from a dead-letter box at Richmond, buried on the beach near Koeberg, and later smuggled into the plant in a car dashboard. The operation was slick and successful and caused damage of R13 billion at today’s prices. Wilkinson was audacious but nervous and steadied by Gray. He later attributed his smuggling skills to dagga smoking and his anticipative ability to being a champion fencer.

Then in May 1983, the emphasis changed with a car bomb attack on the headquarters of the South African Air Force in Pretoria. Premature detonation of 40 kg pf explosives left nineteen dead including the two bombers, Freddie Shongwe and Ezekial Maseko, and 217 injured. In retaliation South Africa attacked Matola in Mozambique. The TRC was to declare this an act of war, but it was arguably a disproportionate act of terrorism planned in the certain knowledge that civilians would suffer.

A similar trajectory would unfold in Natal in the first part of 1986 when Durban became known as bomb city. A Special Ops cell headed by Gordon Webster, who trained in Angola, drew recruits from the complex coloured community of Wentworth such as Robert McBride and Jeanette and Greta Apelgren. Webster had been at school in Pietermaritzburg at Haythorne High and returned to South Africa in October 1985. He used a graveyard in New Hanover to cache explosives and grenades under a headstone. Operations were conducted against electricity, water and oil infrastructure. Jacobs sub-station in Durban was hit twice, plunging Wentworth into darkness. Labour Party figures were targeted and a hoax bomb placed in a parkade in Pine Street, shutting down Durban city centre. The Mobil pipeline burned for twelve hours. The group displayed great ingenuity, adapting vehicles and making limpet mines more difficult to defuse.

Then there was the daring and remarkable rescue worthy of a film of Webster from Edendale Hospital on Sunday 4 May 1986 by the McBrides, apparently inspired by Soledad Brother. Webster and Bheki Ngubane had been spotted by police en route to bomb a Mooi River substation on 27 April; the latter being shot dead. The rescue was enabled by inside sympathisers and enacted by Robert and Derrick McBride disguised as a doctor and priest respectively. Premature shooting broke out and Webster, unable to walk, was snatched from ICU, transported initially on a laundry trolley shooting at the ceiling with an AK47. Hospital staff cheered, sang and ululated. Although a decoy grenade attack did not materialise, Webster was transported to Wentworth and Mlazi, then successfully evacuated to Botswana in another feat of ingenuity using a caravan with secret compartments. The Webster/McBride unit moved fast and showed impressive technical skills, although for some it took too many chances.

But then with the fifteenth of eighteen Natal operations, things fell apart as they had in the Transvaal. It was decided to target security forces off duty in a civilian environment. Such was the Why Not (Magoo’s) bar car bombing on the Durban beachfront on 14 June 1986 in which three civilians died.

Elsewhere there were two remarkable solo operations involving no loss of life. In March 1986, Marion Sparg successfully bombed John Vorster Square, security police headquarters in Johannesburg. This was an audacious operation and perhaps the most symbolic of Special Ops successes for activists: Ahmed Timol and Neil Aggett had been murdered there. She also bombed two other police stations, Cambridge (East London) and Hillbrow, although the latter limpet mine did not explode. In July the following year Heinrich Grosskopf set off a car bomb by remote control at Wits Command in Johannesburg. Prolonged planning and extraordinary technical imagination adapted an automatic-drive car to operate briefly without a driver. The explosives were set up to avoid collateral damage, but unfortunately the vehicle failed to accelerate as planned and did not reach the wall of the military base. The attack was immensely symbolic, Grosskopf escaped into exile, and it took the authorities months to work out his responsibility.

Another close-knit and ultimately solo outfit was the Dolphin Group (Iqbal Shaikh and Mohamed Ismail), which conducted 35 operations without detection in Gauteng, although some of these were low-key and mundane enough to raise questions about whether the unit fitted the definition of Special Ops. Like other units it benefited from apartheid racial profiling and as with whites, Indian saboteurs enjoyed some leeway in moving around without suspicion.

The Ellis Park stadium bombing of July 1988 commanded by Lester Dumakude raised again the wisdom of choosing targets symbolic of apartheid, in this case rugby, that ran the high risk of civilian casualties. There is dispute about operational detail, but two people died. The attack on the offices of the Witbank security police three months later also used a car bomb. Police were legitimate targets, but their offices were inaccessible so a daytime bomb outside was chosen by Xolile Sam. Predictably, it killed three people, none of them police.

Carrim also covers operations that were planned, but not carried through for various reasons: Umfolozi Bridge, the Durban-Johannesburg oil pipeline, Upington bridge, a tanker in Durban harbour, a military transport plane flying out of Swartkop, Sasol yet again, and another widespread blackout; for reasons that varied between incomplete reconnaissance, lost plans, faulty materiel, bad luck and inappropriate or malfunctioning (possibly sabotaged) equipment.

There was also humour: bemused police reactions to a shackled Sparg drinking tea in their stations; whites in vehicles sitting on arms and explosives being totally ignored; police twice assisting the vehicle carrying Grad-P equipment and complaining about the weight; a stolen car ordered that turned out to be a cousin’s.

Special Ops attracted a share of criticism such as its precise relationship with mass struggle; its autonomy and demand for resources; definitions of some operations that appeared similar to the lower level (potboiling) attacks typical of regional units; and the distance between its leaders and operatives on the ground. After the Nkomati Accord of 1984, Special Ops lost its Maputo base. Emphasis shifted to infiltrating arms on a large scale to sustain a people’s war. The safari truck operation made forty trips each with a one tonne load. But nonetheless in the early 1980s Special Ops high visibility attacks had made a significant impact and marked a turning point in the struggle.

There is no doubt that the armed struggle had moral weight and could be justified in international law. Apartheid as a doctrine was a crime against humanity and during the 1980s the South African government brazenly abandoned any semblance of the rule of law by adopting terrorist tactics. MK Special Ops involved remarkably few civilian deaths compared with the fatalities inflicted by apartheid. Infrastructure and military and police targets were fair game. Enormous bravery and resolve were shown by Special Ops, but a few operations were highly questionable and deserve hard scrutiny: those that aimed at security forces in civilian settings. Justification for collateral fatalities was woefully thin and civilian casualties probably did more harm than good. The use of car bombs, notoriously imprecise and unpredictable, was extremely unwise.

An important issue to emerge from this impressively well-researched and presented account is the non-racial composition of Special Ops, which also included a number of foreign recruits (internationalists who often preferred to be called cosmopolitans). Most were members of anti-apartheid movements in Britain and Europe who had grown up in the 1960s, many with parents who played significant roles in World War Two. This was in part tactical: non-Africans and white women in particular were less likely to be suspected by South African security forces. A dare-devil attitude and spirit of adventure infused all Special Ops members. And the regime hindered itself by racial profiling and assumptions based on it.

But the unit also represented a fundamental belief in non-racialism that has been steadily trashed to a point of non-existence by the ANC over the last thirty years. Many of those who risked their lives would be of no significance whatsoever in today’s ANC. A significant number of operatives look back nostalgically to a unique time of moral purpose and clear commitment to what was right at the time regardless of what has transpired since. This might apply to many members of the anti-apartheid struggle in general.