NOTHING appears to separate the worlds of Cyril Ramaphosa and Jacob Zuma more obviously than their attitudes towards the Zondo Commission into State Capture. Ramaphosa turned up for two apparently co-operative rounds; Zuma when he did deign to arrive gave a virtuoso performance of victimhood. Desperate to avoid Paul Pretorius’ penetrating questions, he eventually ended up in prison for non-co-operation, even though Judge Zondo bent over backwards to accommodate him. This provided yet another catalyst for ongoing insurrection by the politico-criminal tendency known as the RET (radical economic transformation) faction.

So Ramaphosa obliged. But his responses were unconvincing even when he did provide a straight answer. The main question during his two-day appearance as state (as opposed to ANC) president was what he had known and what he been doing during his four-year stint as deputy president to the venal Jacob Zuma whose outrageous behaviour amounted to treason.

The answers seemed to be very little; and not much. Ramaphosa is reputedly a practitioner of the long game, a polite phrase for masterly inactivity. Seemingly, he was largely unaware of the graft and corruption, the looting of the public fiscus, the root and branch destruction of key public institutions, and the persecution of whistleblowers under the Zuma administration. Was he blind and deaf to miss what we were all reading in the newspapers and hearing from civil society organisations? Ramaphosa was also apparently struck speechless. The long game clearly has well-disguised depths that dull the senses.

Unimpressive does insufficient justice, but we should not be surprised. And the essential clues lie in the culture of the ANC. Origins are to be found in the apartheid years in exile. Like other liberation movements it became a surrogate family for many people, providing finance, education and training, and psychological support in alien surroundings. This dependence became entrenched and blended with the patronage traditionally dispensed by uBaba and uMama.

This was bolstered by East European and Soviet ideology. Leninism involved placing a vanguardist party above the state: the party is the nation and the nation is the party; thus the utterly disastrous policy of cadre deployment. Dependence and patronage, political ideology and traditional attitudes have moulded the ANC; mixed together with black African nationalism. The outcome is often in direct conflict with the provisions and spirit of the Constitution.

Rhetoric aside the ANC has taken the traditional path of liberation movements. Any likeness to a political party is purely coincidental. It is now a thoroughly corrupt business in which politics mixes with criminality that works in two dimensions: first to reward political bosses; then to cascade largesse to their followers. This explains the violence that plagues the ANC. Electoral success and job appointments are primarily not about service, but access to loot and opportunities to plunder. Those who lose out are strongly tempted to eliminate competitors and often do just that.

Challenges to this endemic system are met with robotic responses. Court judgements that (invariably) go against the ANC are studied at length and then appealed in a process of endless lawfare. Policies and initiatives are endlessly launched to much fanfare, but without action. Accusations are made, Cold War-style about agents and traitors. Hard truths are simply ignored.

Tactical violence was all-too evident in the run-up to municipal elections held on 1 November. And there were other instructive events. In the Copesville ward of Msunduzi (Pietermaritzburg) the ANC correctly removed the preferred candidate according to its stand-down rule as he faces corruption charges; but gave in to popular pressure and re-instated him. Corruption is popular ‒ it benefits many people. And those who lose out can dream that the system, give an assassination or three, may one day benefit them.

Campaigns were attended by the sort of publicity most countries would associate with a general election. Manifestoes were launched at grand events for a level of government that should be limited simply to delivery of basic utilities. And, in a sense, the elections were irrelevant. A minor political earthquake means that in many municipalities the ANC now has to seek coalition partners with parties mostly as corrupt as itself. One hopeful place is uMgeni (Howick, Mpophomeni and Hilton) where the Democratic Alliance has taken control for the first time ever of a KwaZulu-Natal municipality. How the DA copes with layer upon layer of accrued corruption and incompetence now embedded and systemic will be highly instructive. A well-rooted political culture has first to be excavated and then replaced ‒ quickly. Will its beneficiaries stand quietly aside? Experience of a quarter of a century of supposed democracy suggests that obstruction, if it does not thwart reform, may soon be replaced by violence.

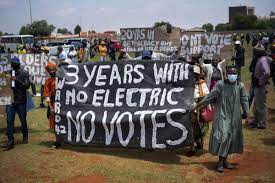

Grim fact is countered by pure fantasy. As a result of lack of planning and widespread corruption South Africa has now suffered under unreliable electricity supply for thirteen years. No country can prosper in the modern age uncertain about power. Yet the rhetoric about computerised cities and the so-called fourth industrial revolution is totally divorced from blackout reality. The culture of the ANC belongs to a number of historical eras and places. Unfortunately, none of them are suited to the needs of a country in a globalised world of the early twenty-first century.

One of the indications of the void into which the ANC has plunged is treatment of its own history. Robben Island, Lilliesleaf Farm at Rivonia and the Brandfort house to which Winnie Madikizela Mandela was banished are all, together with other monuments, in a state of shambles and financial disarray. Looting, it appears, knows no bounds, not even one’s own legacy. In the Eastern Cape a politician faces charges for stealing from funds allocated to Nelson Mandela’s funeral. Meanwhile, back at Luthuli House in Johannesburg, the ANC’s headquarters, the continent’s oldest and most influential liberation movement cannot even pay its own staff, who are now, it is rumoured, on their own thieving campaign.

It all boils down to political culture that lacks moral content. In the process of hollowing out the State for personal and group gain, the ANC has allowed the last vestiges of civic responsibility to be leached from its own being.