THURSDAY 26 June marks the seventieth anniversary of the adoption of the Freedom Charter at Kliptown in 1955. A document about which there has been much debate, it is undoubtedly one of the most inspirational in South Africa’s history. A more specific argument involves its genesis. Was it the product of the aspirations of thousands of repressed South Africans, the pens of a few clandestine communists, or possibly both? This may never be resolved.

The Charter was a direct challenge to the divisiveness of apartheid in its opposition to injustice and inequality and promotion of equal rights and opportunities. Much of its language is redundant: ‘national groups’, for example. Similarly, the term ‘will of the people’ has lost much of its force and legitimacy, hijacked by authoritarians.

Many of the aspirational aspects of the Charter are now redundant. Post-apartheid South Africa has shown it lacks the civic duty and commitment necessary to run nationalised industries. It requires little imagination to see what would happen if the policy of populist parties seeking to requisition land were adopted. The fate of VBS is stark warning of the fate of nationalised banks, mining companies and manufacturing. State-owned enterprises are among the most corrupt and worst run of the nation’s institutions. The Charter calls for land rights and agricultural extension, but this has been another area of limited success. Likewise, the idea of the police as helpers and protectors of the people will be novel to the millions who pay for armed response private security.

However, the rule of law and basic human rights ‒ such as those to speak, organise, meet and publish ‒ are well entrenched; although whether discriminatory law has been abolished, and there is equality before the law in certain areas, is arguable. Equal pay has certainly not been achieved and other unacceptable labour practices can still be found. The hopes for school education – universal and equal ‒ have been squandered, in part by unprofessional and politicised unions. The same story is true of health and care of the elderly. And the idea that South Africa could be a leader in moves towards world peace, realistic during Nelson Mandela’s presidency, now seems bizarre given our links to Russia and Iran in particular (China too) within BRICS. We are close allies of some of the most repressive regimes in the world. It is hardly a stellar record.

But the Charter is a noble document that has greater and greater relevance with each ratcheting up of global right-wing populism. It is a statement of diversity, inclusivity and bridge building that develops out of the opening statement that South Africa belongs to all those who live in it. At the time it was a powerful counter to apartheid; but it has equal validity today in the context of the ascendancy of illiberalism and neo-fascism.

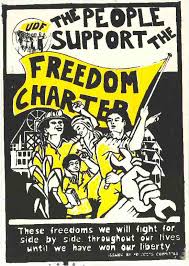

Following adoption of the Charter and its insistence that there should be no distinction of colour, race, gender or belief, the concept of non-racialism went from strength to strength. It became the main driving force of the internal resistance to apartheid particularly through the United Democratic Front, South Africa’s most inclusive political movement of all time. Ostensibly, the ANC also subscribed to non-racialism but it has steadily been eroded, even derided.

In a cynical, post-truth world in which evil is increasingly normalised, documents like the Charter are a valued reminder that in a context of lies, fake news and conspiracy the distinction between good and bad, rational and irrational, just and unjust and many other polar opposites is blurred if not dissolved. The civic centre of gravity vanishes and opportunists, charlatans and narcissists flourish.

While much of the detail of the Charter might be of largely historic interest it retains a strong degree of socio-political morality. In this world of increasing extremism, we need as many sources of liberal inspiration as possible especially those well grounded in past struggle.