The prolific Scottish writer M.C. Beaton (Marion Chesney) described libraries as ‘palaces of dreams’. Looking back over fifty years of working life and four careers, they all had their highlights. But only libraries carried a distinctive sense of place, whether I was there as employee or as a user. They have, or used to have, their own distinctive personality dependent on architecture and layout, holdings, and the people – readers (yes, readers) and staff. Nowadays many of them, not all thankfully, have the sterile atmosphere of an internet café. No other place of work in my experience had the aura of a library; newsrooms can be exciting places but could be anywhere and are a product of specific people and memorable events.

A quick tally brings to mind two dozen libraries and archives I have used across sixty-plus years and there are no doubt quite a few more. They range from converted school classrooms to enormous university and national libraries. It would be tedious to describe most of them, so I’ll limit this to just three: the library of St Edmund Hall, Oxford; the School of Oriental and African Studies library in London; and the University of Natal (Pietermaritzburg) library.

The SEH library is the deconsecrated church of St Peter-in-the-East, which falls within the walls of the college. College libraries tended to be small because during the day we had departmental facilities to use and every weekday I booked my place at the School of Geography library. Some people preferred to work in their rooms. The SEH library was particularly alluring in the evening with its downlit tables, high rafters and antiquity. There was a sense of close community and, not surprisingly, of monasticism. It was basically a place of study and the book stock certainly held no interest for me.

After finals, I didn’t leave Oxford immediately but stayed on for a while at the request of my landlady, on urgent business elsewhere, so that her house was looked after. It was a beautiful summer and I spent many hours sitting in the old churchyard reading Russian novels. Some years later, John Kelly and Graham Midgley (and his dog Fred), the principal and dean, would be commemorated by grotesques attached to the tower of the library (pictured).

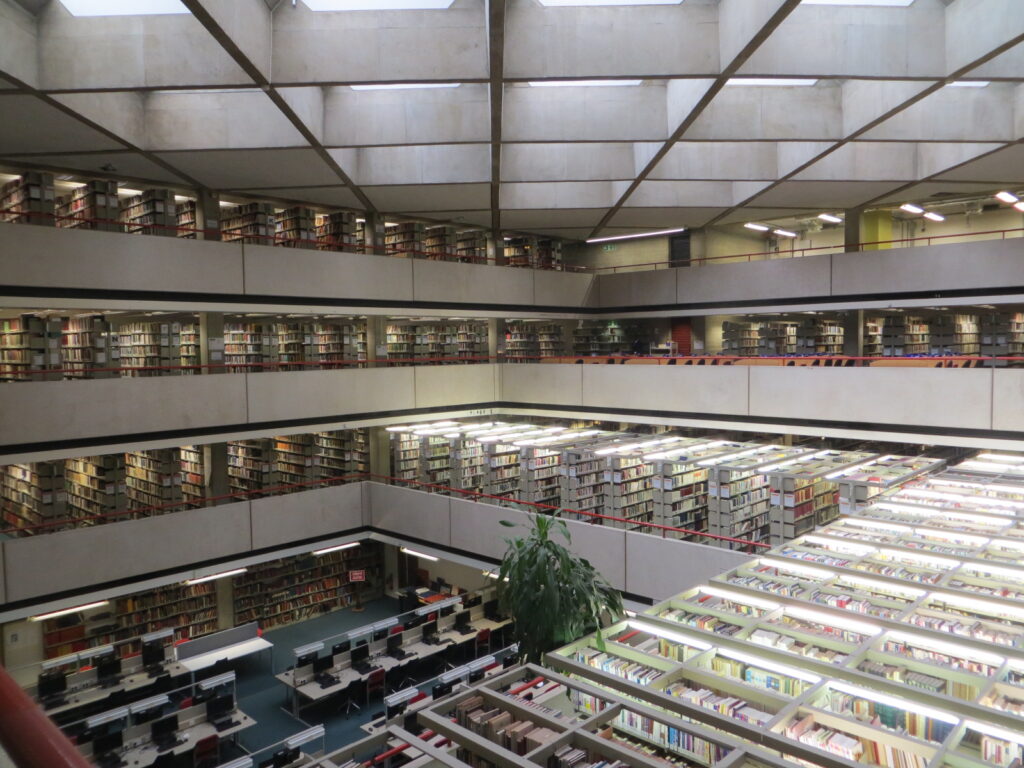

At the end of that summer, I moved to London and my first job as a librarian. There are those who were unimpressed by SOAS library but it remains pre-eminent in my mind. It had recently moved into an extension at the back of the original building put up in the 1930s. Designed by Denys Lasdun, it had about it a magical feel created by its arrangement of galleries around a central space. The interior was truly remarkable: a deep well at the bottom of which was the short loan reading room looked down upon by three tiers of stacks (pictured). It was a most imaginative design and must have tested the skills of the civil engineers. I was later to discover that if its metal shelving were laid end-to-end, it would stretch from Bloomsbury to Watford. I had particular reason to know this because the deputy librarian gave me the task of measuring it, presumably for some report he had to complete. The library was carpeted throughout and created static electricity. If you touched a shelf, you received a moderate shock; therapeutic or so we were told.

As interesting as design and layout were, the staff were even more so. I have never worked since in such a cosmopolitan atmosphere. Many of the seniors had experienced interesting (second world) wars as linguists or intelligence operatives. Most of the younger staff were single and the resulting social life was memorable. As I was a trainee I came to experience several sections of the library other than periodicals. Evening duties in short loan and frequent stints in inter-library loan were notable. In the latter I worked for a refugee from Idi Amin’s Uganda. It was my task to collect requests from the shelves as fast as possible, many of the books being packaged for Asian-language patients in London hospitals. Several floors and many ranges of shelves provided opportunity for significant conversations.

Had it not been for SOAS I would not have ended up five years and several libraries later at UNP library. I was to work there for 22 years during which the main building gained another floor while staying fully operational, the stock was improved to rival that of much better-endowed libraries, and computerisation was completed in record time. The UNP library was fairly typical of university libraries in the 1980s and 1990s: undoubtedly the hub of the campus. Even on Christmas Eve it was busy. In that era someone commented that a university is just a collection of buildings gathered around a library. Today I occasionally have reason to visit. The book stock remains, largely unused, but otherwise the building has a neglected, funereal air having largely lost its purpose.

Libraries might, and possibly do, provide the setting for fiction. While I was working at University of Cape Town library, a bogus doctor who had apparently successfully practised at Groote Schuur for some while was exposed, having stolen a library book. In Pietermaritzburg, we were constantly aware of courting couples making use of secluded corners. And once while interviewing a candidate for a post at Law we asked, ‘Do you know the library at all?’ ‘Well, yes,’ came the answer; ‘I once lived there for a fortnight after being thrown out of my digs.’ She duly got the job.

Some people venerate books and assume that a pile of dusty of old tomes has enormous value and should send a librarian into raptures of delight. Most of the time as long as there is a national depository, actual or virtual, those piles might as well be incinerated. Indeed, the very worst donation one might make is of a collection of dog-eared, out-of-date books to a school library; sufficient to kill any child’s interest in reading. It happens frequently.

The rise of alternate, electronic technologies has shown that books remain the most appealing and effective way of communicating prose. Books still sell. Serious readers do not favour any electronic form unless they have particularly poor eyesight and Kindle is in deserved decline. The instinct to own a book rather than rent a copy is still strong: they can be donated, shared, loaned or stored away for future reference. Nothing in this world is permanent, but online versions are particularly vulnerable to loss. And the books that are important to us are an integral part of each individual.

The palace of dreams is not a place of sacred objects; but a living and working collection that inspires imagination, creativity and self-development. Those of us lucky enough to have been employed in libraries have double confirmation of that. Many writers have had their say, for example Jorge Luis Borges: ‘I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of library.’ Others have been more philosophical. Ray Bradbury argued that ‘without libraries … we have no past and no future’; while T.S. Eliot saw in them ‘hope for the future of [hu]mankind’.

Libraries are rapidly disappearing in the true sense and increasingly becoming unstable, unreliable electronic hubs. Exactly where does that leave humanity?