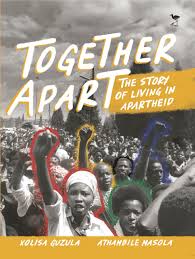

Xolisa Guzula and Athambile Masola, Together Apart: The Story of Living in Apartheid (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2024)

NO one under 35 can have a first-hand understanding of life in apartheid South Africa. To many of today’s children it is no doubt simply an historical term; to some just meaningless. That makes Xolisa Guzula and Athambile Masola’s history written for young people particularly important.

It takes a picture book approach in which four children pose questions to Makhulu about her experiences. These are interspersed with sections on topics such as pre-colonial society; the colonial wars of dispossession; segregation; apartheid and anti-apartheid organisations; forced removals and the bantustans; and labour, sport and culture.

The graphics are bold and colourful and avoid caricature. Timelines are used to good effect; while the language used is straightforward although in places it becomes misleading. In the case of the millenarian story of Nongqawuse and the Xhosa cattle killing there is a degree of wild speculation. Another wayward interpretation is to regard the United Democratic Front as ‘based on Christian values’ and ‘not associated with the struggle’. It was multi-faith, while strongly influenced by Christianity; and was very much part of the struggle, but not the military one. Nor was Ahmed Timol’s the first death in detention; or friendship across race lines prohibited, although it was made as difficult as possible.

Great effort has clearly been put into design, layout and context. But there appears to have been no proof reading. Had there been, factual errors such as 1880 as the date of the battle of Rorke’s Drift and Alan (rather than Allan) Boesak would have been avoided. Similarly, the content of a table headed 1855‒1946 starts in 1886. The pages of the section on the 1956 Women’s March are illogically placed; and a table on censorship legislation is upside down, back-to-front and has major omissions. A list of trade unions does not differentiate between federations and individual organisations.

Some topics are given surprisingly little, or no, space: the Soweto uprisings (of children) in 1976 and the Durban strikes of 1973 and FOSATU are examples. Sport is over-represented and error-prone: SACOS was the Council on Sport; Basil d’Oliveira was not banned from playing cricket in his home country; and the game was not first played in 1890. In the sporting context, black is assumed to be African.

Both writers are from UCT and there is a decided Western Cape bias. Books like this are notoriously difficult to produce, but this one falls short in significant ways.