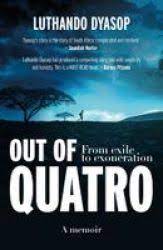

Luthando Dyasop, Out of Quatro: From Exile to Exoneration (Cape Town: Kwela, 2021)

ONE Saturday afternoon in 1980, Luthando Dyasop left home in Mthatha on foot. A week later after a circuitous journey he arrived at Qacha’s Nek to join the ANC in Lesotho. The circumstances of his departure are somewhat opaque. His forte was drawing and painting with a childhood that was relatively liberated for the time: for a while he had as a friend a white girl. He accompanied his father on enjoyable work trips to Queenstown and the Wild Coast that involved building repair and decoration, but then had a fall-out. He accused a friend of spying on him on behalf of the Transkei authorities. And his mother had him committed to a psychiatric unit for a few months. His ambition was to become an architect, a profession then closed to black South Africans. And, like many young Transkeians, he was opposed to the puppet government of the Matanzima brothers.

Exactly how all this contributed to a decision to go into exile is not entirely clear, but at the age of 22 he was enrolled in the ANC. It was already an organisation in trouble with discipline problems stemming from poor standards among officials, confused purpose and a harsh security apparatus. Nevertheless, Dyasop maintained his enthusiasm and travelled via Maputo to Angola to train with MK. This seems to have been successful and like many volunteers he looked forward to returning home to fight for freedom. Instead, MK soldiers became just another pawn in the Cold War fighting against UNITA. This was not what they had signed up for, and they mutinied.

By February 1984 Dyasop and his comrades were at Viana camp where they were attacked by Angolan FAPLA forces at night time. He fired on an APC with a rocket launcher and killed the driver, but surrender and imprisonment in Luanda followed. From there transfer was made to ANC security (Mbokodo) and to Quatro. This is the kernel of Dyasop’s book, although it has long been well documented. He describes his four-year detention as ‘an underground river of tears that is deep’ (137); days in hell in a place whose name signifies anguish.

Dyasop and his comrades were denied due process or treatment that conformed to the rules of war even though the ANC had signed the Geneva Convention. Instead, they were labelled enemy agents (sound familiar?) and subjected to daily beatings by sadistic East German and Soviet-trained guards. This went on beyond all reason: what purpose was served by assaulting men while they were trying to move a 1,000-litre water tank uphill or collect massive amounts of firewood? This was slave labour punishment and culminated in a Christmas Day nightmare: ‘Just being in Quatro was torture,’ writes Dyasop. And his wonderment extends to questioning ‘the unhesitating readiness of a black person to harm another with such zeal’ (142). They were, after all, supposedly fighting for the same ideal: the liberation of South Africa. Dyasop was himself beaten into unconsciousness and suffered fits.

His verdict is that Quatro was ‘the ANC’s version of a Nazi concentration camp … or … the Gulag of the Soviet Union’ (159). He equates the brutality of apartheid and ANC security: ‘complete disdain for the law, humaneness, ethics and morality.’ A visit to Quatro by Chris Hani in February 1985 changed little. The architect of Quatro was Mzwandile Piliso and the Kabwe conference strengthened his malign influence and that of Joe Modise. Oliver Tambo visited in August 1987 after which Dyasop and his fellow detainees were put to work on construction to expand the camp. United Nations Security Council resolution 435 and the run-up to Namibian independence required the ANC to leave Angola, but Quatro’s inmates were sworn to secrecy about their experience there.

Dyasop ended up at Dakawa camp in Tanzania where the conflict between democrats, represented by Omry Makgoale, and Piliso and the securocrats continued to play out. Dyasop was again involved in building work, but also art and boxing. In the case of the last he was able to engineer a match so that a former torturer received a thumping from a Tanzanian boxer. But events at Dakawa showed that a jackboot legacy would prevail over self-expression and democracy. The torture of dissidents continued. So, in December 1989, fourteen Dakawa residents abandoned the ANC and its ‘polarised guerrilla army’ and ended up in Malawi, returning home in 1990 where Dyasop and others were held for a while by the police security branch at Barkly West. Once free they called for an inquiry into abuse and atrocities in ANC camps and were attacked by Jacob Zuma. Back home in Mthatha an attempt was made on Dyasop’s life and his friend Sipho Phungulwa was shot dead. Of this episode Dyasop writes damningly, ‘It continued the pattern of an army that never engaged its enemy in a decent battle but found it not difficult to eliminate one of its own’ (208). The name of Chris Hani appears a number of times in this book in an unflattering light.

True to form the ANC was involved in a number of investigative commissions most of which muddied the waters, although Dyasop felt vindicated by Skweyiya’s. He received help from Frank Chikane; and then from John Deere and the British consulate in setting up a brickmaking business called A re Ageng, but this foundered on corruption surrounding Reconstruction and Development Programme housing. His brief spell as a staff sergeant in the new army ended when he had to go AWOL to attend his mother’s funeral; and finally he decided to become a full-time artist. In the meantime, he testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) only to find that crucial parts of his statement had been ignored. He also casts doubt on the amnesty proceedings around three of Phungulwa’s killers and suggests that the TRC was influenced by ideological bias.

Dyasop has done an excellent job on a painful topic and honoured the names of those he feels were used and abused by the ANC. Clearly the writing of this autobiography was a cathartic experience. Above all, the evidence he presents gives good reason to consider the inadequacies of the ANC as governing party today and relate them to its roots in exile.