Jonathan Lichtenstein, The Berlin Shadow: Living with the Ghosts of the Kindertransport (London: Scribner, 2020)

HANS Eugen Lichtenstein, aged 12, arrived alone from Berlin at London’s Liverpool Street station in mid-1939, one of ten thousand young Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport. (He reckoned it was the last one and that the children involved produced four Nobel prize winners.) Having qualified in medicine, he served in the British Army in Malaya, and then settled as a doctor in Radnor in the Welsh borderlands.

The centrepiece of this book, written by his son the academic and playwright, is a reverse journey as precise as possible in Hans’s eighties to Berlin to find the graves of his father and grandfather, his father’s shop attacked on Kristallnacht in 1938, and various other landmarks of childhood and the pre-war journey by rail and sea. Jonathan accompanies him and reflects on the effect on his own life of his father’s character, background and experiences.

Hans survived the war as did his sister Toni (in Holland) and his mother Ruth (in Germany, reclassified under the Mischling law). They were in luck, but relatives perished in the Holocaust. Hans’s father, grandfather and an uncle all committed suicide before or during the war. Jonathan reflects that ‘as a family [there were six children], we unwittingly inhabited for lengths of time an unknown, inexplicable world fill of silences and unspoken loss.’ This ‘history of immigration’ is reflected in Hans’s very British clothes; ‘the garments of disguise’.

He suffered nightmares and would disrupt the family by cleaning the house in the middle of the night. Coping with the past involved a life of action, believing the body should simply obey the mind’s orders. Stillness was anathema. He was a pathologically reckless driver and took deliberate risks in his dinghy, endangering the lives of his wife and children. Jonathan concludes that Hans inhabited a different world, set apart, fighting to remain part of life in general and fearing another removal: ‘Something was stolen from him on that train journey and it cannot come back.’ Having experienced partial extinction, another more secure life had to be created.

As a child Jonathan was a victim of his father’s overbearing manner. Desperately ill with pneumonia, his doctor father tells him to ‘stop making a fuss … I’ve seen much worse’. Instead of putting him in hospital he suggests he go back to school. Hans’s parental methods could now be seen as child abuse. For petty misbehaviour, he threw Jonathan, unable to swim, into a pool and seems to have left him to drown.

Jonathan and his father, even on the return journey to Berlin, have enormous difficulties in communicating. But clearly part of the father had rubbed off as Hans intended, with a shared liking for extreme moments to prove they were still alive. And the Berlin trip clearly contributed to rapprochement.

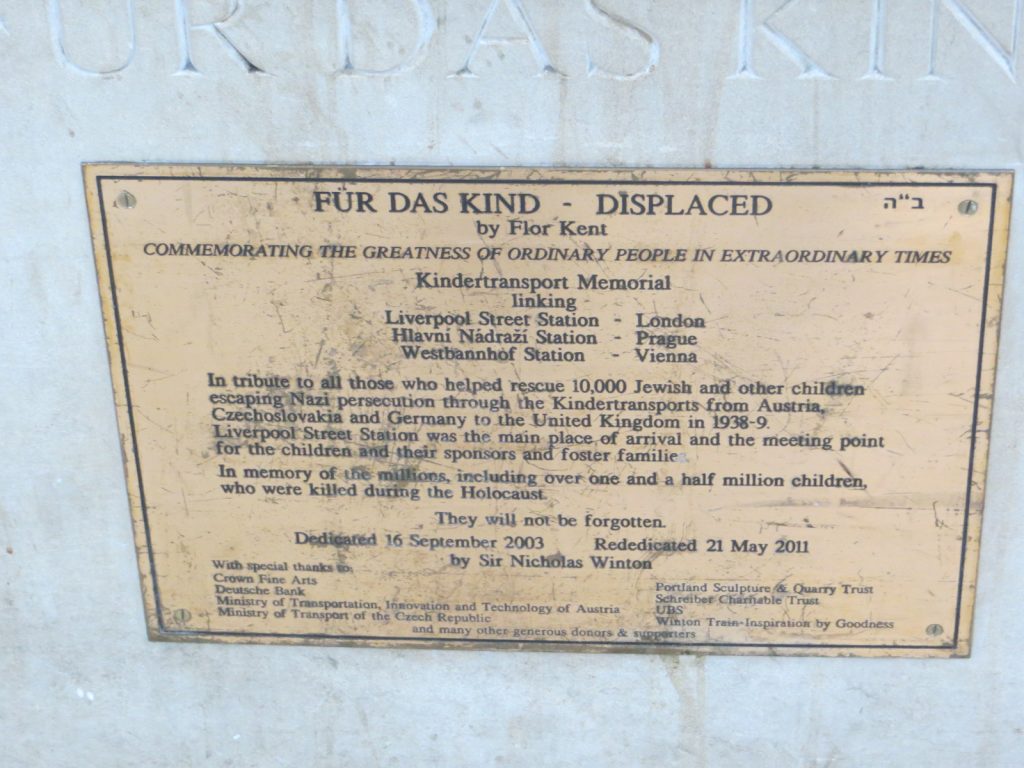

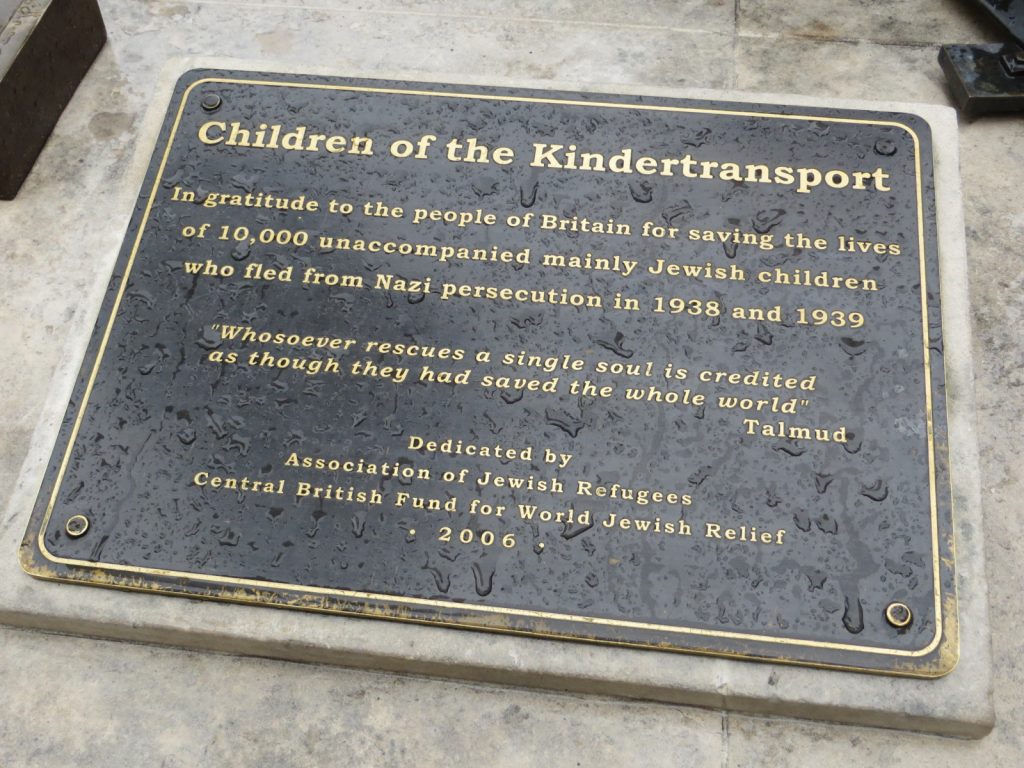

This is a work of literary psychology; and thin on dates or references to time. But the journey seems to have taken place about seventy years after Hans’s train reached London. It is remarkable how many landmarks remain to remind him of a lost life and the journey that removed him from it. In and around Berlin he visits the Jewish Museum and the remains of Sachsenhausen, the first Nazi concentration camp, with remarkable fortitude. The last part of the journey he travels alone by train from London home to Llandrindod, after visiting the two striking memorials to the Kindertransport at Liverpool Street station.

And after an early life of peril and later frenetic, compensatory activity even into old age, Hans died a quiet death at 91 last year. His peaceful end, we may assume from his son’s book, owed much to the cathartic return journey to Berlin and a coming to terms with its shadow.

• Reviewer’s note: my maternal grandfather worked for most of his life at Liverpool Street station in a clerical job for the Great Eastern Railway. His office overlooked the platforms, but not I suspect those for the trains from Parkeston Quay, Harwich. He was definitely there in 1939 and, I would like to believe, saw the arrival of the Kindertransport. The photographs taken at Liverpool Street station are by the reviewer.